The Return Guarantee Trap: What No One Tells You About Debt Crises

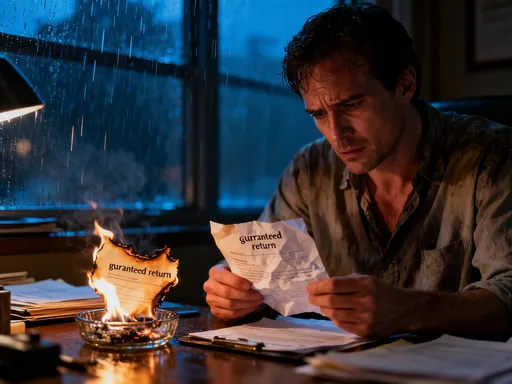

When debt piles up, the promise of a "guaranteed return" feels like a lifeline. Many people have chased that promise—only to sink deeper. In times of financial stress, we’re drawn to solutions that sound too good to be true. And often, they are. This is not about quick fixes or magic formulas. It’s about what really happens when you bet your recovery on returns that aren’t guaranteed. The allure of stability in uncertain times is powerful, but the reality is that no investment is immune to market forces, institutional failures, or personal misjudgments. Let’s walk through the real risks, the hidden pitfalls, and the smarter path forward—grounded in experience, supported by data, and focused on lasting recovery rather than temporary relief.

The Allure of Guaranteed Returns in a Debt Crisis

When individuals face overwhelming debt, the appeal of a guaranteed return becomes almost irresistible. It speaks directly to the emotional core of financial distress: the need for certainty. In moments of anxiety, where monthly payments loom and savings dwindle, the idea that a financial product can promise a fixed, predictable outcome feels like an anchor in a stormy sea. This psychological comfort is precisely what drives demand for instruments labeled as "safe," "insured," or "guaranteed." But beneath this surface-level reassurance lies a complex web of conditions, limitations, and unspoken risks.

Marketing plays a significant role in amplifying this allure. Financial institutions often present certain products—such as structured notes, fixed annuities, or principal-protected funds—as foolproof solutions for those seeking stable returns. These offerings are typically promoted with clean visuals, simple language, and bold claims about performance protection. What is less emphasized, however, is the context in which these guarantees hold. For example, a structured note may promise 100% principal protection, but only if the issuing bank remains solvent and the underlying market conditions do not trigger early termination clauses. In a systemic crisis, even these safeguards can fail.

The psychological draw of guaranteed returns also stems from cognitive biases. One of the most relevant is loss aversion—the tendency for people to feel the pain of a financial loss more intensely than the pleasure of an equivalent gain. When debt mounts, the fear of further loss dominates decision-making, leading individuals to prioritize capital preservation above all else. This mindset makes them vulnerable to products that claim to eliminate risk entirely. Yet, in practice, eliminating risk often means accepting very low returns, which may not be sufficient to outpace inflation or make meaningful progress against growing debt.

Another factor is the misinterpretation of what "guaranteed" actually means. Many consumers assume the term implies absolute safety, backed by government or regulatory authority. While some guarantees are indeed backed by agencies like the FDIC up to certain limits, many others are only as strong as the institution providing them. During the 2008 financial crisis, for instance, several financial products marketed as secure collapsed when their issuers faced insolvency. Investors who believed their returns were protected discovered too late that the guarantee was conditional and dependent on broader economic stability.

The pursuit of guaranteed returns during a debt crisis can also lead to opportunity costs. By locking funds into low-yield, supposedly safe instruments, individuals may miss out on more effective debt-reduction strategies. For example, someone might keep money in a fixed deposit earning 2% annually while carrying credit card debt at 18%. Over time, the cost of the debt far exceeds any return earned, making the "safety" of the investment counterproductive. The emotional appeal of predictability thus comes at a real financial price—one that is often overlooked in the moment of decision.

Why “Guaranteed” Isn’t Always Safe

The word "guaranteed" carries immense weight in financial communication, suggesting reliability and security. However, in the world of investing and debt management, it rarely means what it seems to imply. A closer examination of financial guarantees reveals that they are often conditional, limited in scope, or dependent on the solvency of the institution making the promise. Understanding the fine print behind these guarantees is essential for anyone navigating a debt crisis, where the consequences of misplaced trust can be devastating.

One of the most important distinctions to make is between government-backed guarantees and those issued by private institutions. In the United States, for example, deposits in banks insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) are protected up to $250,000 per depositor, per insured bank. This protection is real and has been honored consistently since the agency’s creation in 1933. However, this level of security does not extend to most investment products. A "guaranteed return" offered by an insurance company, a brokerage, or a private fund is only as reliable as the financial health of that entity. If the company fails, the guarantee may become unenforceable.

Historical examples underscore this risk. During the 2008 global financial crisis, many investors held products linked to Lehman Brothers, including structured notes and guaranteed investment contracts. These instruments promised fixed returns and principal protection, but when Lehman collapsed, the guarantees vanished. Holders of these products faced significant losses, not because the underlying assets failed, but because the issuer could no longer honor its commitments. This illustrates a critical point: the guarantee is not on the asset, but on the promise-maker.

Another common limitation is the presence of conditions that void the guarantee. Some products offer returns that are guaranteed only if certain criteria are met—such as holding the investment for a specific period, not making early withdrawals, or avoiding market-linked triggers. For instance, a fixed annuity might promise a 5% annual return, but only if the contract is held for ten years. Withdrawing funds earlier could result in surrender charges, reduced payouts, or the complete loss of the guarantee. In a debt crisis, when liquidity is often urgently needed, such restrictions can render the "guarantee" practically useless.

Liquidity risk is another hidden danger. Even if a return is technically guaranteed, accessing the funds when needed is not always possible. Some guaranteed products have long lock-up periods or require notice before withdrawal. In times of financial emergency, this lack of flexibility can force individuals to sell at a loss or borrow at high rates elsewhere, undermining the very purpose of seeking safety. The illusion of security is shattered when the money cannot be accessed when it is most needed.

Furthermore, inflation can erode the real value of a guaranteed return. A product that promises a fixed 3% annual return may seem safe, but if inflation runs at 4%, the investor is effectively losing purchasing power each year. This is particularly problematic for those using such returns to pay down debt, as the real cost of borrowing may still exceed the real return on investment. The nominal guarantee does not protect against this silent form of loss, which accumulates over time and is often invisible in the short term.

The takeaway is clear: a guarantee is not a blanket shield against loss. It is a contractual promise with specific terms, limitations, and dependencies. Relying on such promises during a debt crisis—especially when under financial pressure—can lead to misplaced confidence and poor decisions. True financial safety comes not from the label on a product, but from a thorough understanding of its mechanics, the strength of the issuer, and the alignment with one’s actual financial needs and timeline.

The Hidden Costs of Chasing Returns to Pay Off Debt

On the surface, using investment returns to pay off debt appears to be a logical strategy. The idea is simple: grow your money through safe investments and use the gains to reduce what you owe. However, this approach often fails in practice due to a combination of timing mismatches, fees, taxes, and behavioral biases. The hidden costs of chasing returns can outweigh the benefits, leaving individuals further behind than if they had focused directly on debt reduction.

One of the most significant mismatches is between the time horizon of investments and the urgency of debt payments. Many guaranteed or low-risk investments require several years to deliver their promised returns. For example, a five-year certificate of deposit (CD) may offer a fixed rate, but withdrawing before maturity incurs penalties. In contrast, credit card bills, medical debts, or personal loans demand immediate or short-term payments. This misalignment means that even if the investment eventually pays off, it may not provide relief when it is most needed. By the time the funds are accessible, late fees, interest accrual, and damaged credit may have already taken their toll.

Fees and expenses further erode the net benefit of return-chasing strategies. Financial products that promise guaranteed returns often come with high management fees, administrative charges, or sales loads. A product offering a 4% return may, after fees, deliver only 2.5% to the investor. When compared to the interest rate on high-cost debt—often 15% or more—the math becomes unfavorable. In many cases, the cost of borrowing exceeds the net return on investment, resulting in a net loss. This reality is frequently obscured by marketing materials that highlight gross returns while downplaying or burying fee disclosures.

Tax implications add another layer of complexity. Investment gains, even from supposedly safe instruments, may be subject to income or capital gains taxes. For example, interest earned on bonds or annuities is typically taxed as ordinary income, reducing the after-tax return. If an individual is in a higher tax bracket, this can significantly diminish the effective yield. In contrast, paying down debt provides a guaranteed, tax-free return equal to the interest rate avoided. Paying off a credit card charging 18% interest is equivalent to earning an 18% return with no risk and no tax liability—a far more efficient use of funds than chasing a 4% taxable return.

Behavioral factors also play a crucial role. The act of investing to pay off debt can create a psychological delay in taking direct action. Instead of making immediate cuts to spending or negotiating with creditors, individuals may tell themselves they are "working on a solution" by putting money into an investment. This sense of progress is often illusory, as the investment grows slowly while debt compounds quickly. The delay can lead to increased stress, missed payments, and a worsening financial position over time.

Additionally, the pursuit of returns can lead to poor asset allocation. In an effort to generate higher yields, some individuals shift funds into riskier instruments—such as high-yield bonds, dividend stocks, or real estate investment trusts—believing they can time the market or avoid losses. However, these assets are not guaranteed and can lose value, especially during economic downturns. If the investment declines while debt continues to grow, the financial hole becomes deeper. This risk is particularly acute for those already under financial strain, who have little margin for error.

Opportunity cost is another hidden expense. Money tied up in low-return investments could have been used to pay down principal, reducing future interest and shortening the repayment period. For example, applying $5,000 to a credit card balance at 18% saves $900 in interest over one year alone. The same $5,000 invested at a net return of 3% earns only $150—after taxes and fees, the gap widens further. The choice is not between earning a return and doing nothing; it is between earning a small, uncertain return and achieving a large, guaranteed savings by eliminating debt.

Risk Control: Protecting Yourself When Everything Feels Uncertain

During a debt crisis, the instinct to seek growth can be strong, but the priority should be preservation. Protecting what you have is often more valuable than trying to increase it. Risk control becomes the cornerstone of sound financial decision-making, especially when uncertainty is high and mistakes are costly. This means shifting focus from chasing returns to building resilience through diversification, liquidity management, and realistic planning.

Diversification remains a fundamental principle, but its application must be thoughtful. For someone in debt, diversification does not mean spreading money across multiple speculative investments in search of higher returns. Instead, it means avoiding overexposure to any single financial product, institution, or strategy. This includes not relying solely on one type of guaranteed return, even if it seems safe. Spreading emergency funds across insured accounts, maintaining some accessible cash, and avoiding overcommitment to illiquid assets are practical steps toward reducing vulnerability.

An emergency buffer is essential. Many debt crises are triggered or worsened by unexpected expenses—a car repair, medical bill, or job loss. Without a financial cushion, individuals are forced to borrow more, deepening the cycle. A modest emergency fund, even if only $1,000 to $2,000 initially, can prevent small setbacks from becoming major crises. This buffer should be kept in a liquid, low-risk account, such as a high-yield savings account, where it is safe and accessible when needed.

Stress-testing your financial plan against worst-case scenarios is another key practice. Ask: What happens if income drops by 20%? What if interest rates rise? What if an investment loses value or a guarantee is not honored? By considering these possibilities in advance, you can identify weak points and adjust accordingly. For example, if a large portion of your recovery plan depends on a single investment return, you may need to revise your strategy to include more direct debt repayment actions.

Assessing personal risk tolerance realistically is also critical. Risk tolerance is not just about how much market volatility you can stomach—it’s about your actual financial capacity to absorb loss. Someone with high debt and unstable income has a lower true risk tolerance than someone with savings and steady earnings, regardless of how "comfortable" they feel with risk. Aligning your financial choices with your real-life constraints, rather than emotional preferences, is essential for long-term stability.

Setting clear boundaries and exit triggers can prevent emotional decision-making. For example, decide in advance how long you will hold an investment, what return you expect, and under what conditions you will withdraw. This removes the temptation to "wait just a little longer" in hopes of breaking even or achieving a target that may never materialize. Similarly, define what level of debt reduction constitutes progress and celebrate those milestones, reinforcing disciplined behavior.

Prioritizing flexibility over yield is a mindset shift that can make a significant difference. High-yield investments often come with restrictions—long lock-up periods, complex terms, or high penalties for early withdrawal. In contrast, more flexible options, even if they offer lower returns, allow you to adapt as circumstances change. In a debt crisis, adaptability is a form of financial strength, enabling you to respond to new challenges without being trapped by previous commitments.

Practical Strategies That Actually Work

While the allure of guaranteed returns is strong, the most effective path out of debt is built on discipline, consistency, and practical action. Rather than relying on uncertain financial products, individuals can make meaningful progress through proven, repeatable strategies that focus on improving cash flow, reducing interest costs, and changing financial behaviors.

One of the most powerful steps is renegotiating terms with creditors. Many people assume their interest rates and payment schedules are fixed, but in reality, creditors often have some flexibility, especially if a borrower is at risk of default. Calling lenders to request lower interest rates, extended payment terms, or temporary hardship programs can lead to significant savings. For example, reducing a credit card rate from 22% to 15% can cut interest costs by more than 30%, freeing up funds for principal repayment.

Debt consolidation, when done strategically, can also be effective. Combining multiple high-interest debts into a single loan with a lower rate simplifies payments and reduces overall interest. However, this only works if the new loan has better terms and if the individual commits to not accumulating new debt. Using a balance transfer credit card with a 0% introductory rate, for instance, can provide breathing room—but only if the balance is paid off before the promotional period ends and the rate increases.

Building incremental cash flow is another cornerstone of recovery. This involves redirecting discretionary spending—such as dining out, subscriptions, or non-essential shopping—toward debt repayment. Even small changes, like preparing meals at home or canceling unused memberships, can generate hundreds of dollars per month. These funds, when consistently applied to debt, accelerate payoff and build momentum. Increasing income through side jobs, freelance work, or selling unused items can further boost cash flow and shorten the timeline to freedom.

Adopting behavioral rules helps prevent relapse. One effective rule is the "24-hour wait" before making any non-essential purchase, which reduces impulse spending. Another is the "debt snowball" method, where smaller debts are paid off first to build psychological wins, or the "debt avalanche" method, where highest-interest debts are prioritized to save money. Both approaches work when followed consistently. The key is to choose a method and stick with it, measuring progress regularly.

When to Seek Help—and How to Choose the Right Support

Trying to manage a debt crisis alone can be overwhelming and isolating. There comes a point when seeking professional help is not a sign of failure, but a smart, proactive step. Credit counselors, fiduciary financial advisors, and debt restructuring specialists can provide guidance, negotiate with creditors, and help design a realistic recovery plan. However, not all advice is equal, and some services may do more harm than good.

Red flags to watch for include upfront fees, pressure to invest, promises of quick fixes, or vague performance claims. Reputable credit counseling agencies, such as those affiliated with the National Foundation for Credit Counseling (NFCC), typically offer services on a sliding scale or for free. They focus on budgeting, debt management plans, and financial education—not selling investment products. In contrast, firms that require large upfront payments or push clients into specific financial instruments may be more interested in profit than in genuine help.

Transparency and accountability are essential. A trustworthy advisor will explain fees clearly, disclose any conflicts of interest, and provide written documentation of recommendations. They will not guarantee specific returns or claim to eliminate debt overnight. Instead, they will work with you to assess your full financial picture, set realistic goals, and monitor progress over time. Choosing support based on credentials, reputation, and alignment with your values is crucial for long-term success.

Building Resilience Beyond the Crisis

True financial recovery extends beyond paying off debt—it involves creating a sustainable system that prevents future crises. This means establishing early warning signs, such as rising credit card balances or missed savings goals, and responding before problems escalate. Setting realistic, measurable financial goals—like building a six-month emergency fund or maintaining a debt-to-income ratio below 30%—provides clarity and direction.

Cultivating a mindset focused on sustainability over shortcuts is equally important. Quick fixes may offer temporary relief, but lasting stability comes from consistent habits: living within your means, saving regularly, and avoiding overreliance on credit. Learning from past mistakes without shame allows for growth and improvement. Every financial setback can become a lesson in better decision-making.

Finally, designing a personal finance framework that withstands shocks is the ultimate goal. This includes automating savings, using simple and transparent financial products, and regularly reviewing your plan. Resilience is not about avoiding risk altogether—it’s about being prepared, informed, and empowered to navigate challenges with confidence. By focusing on what truly works, not what merely sounds good, individuals can move from survival to strength, and from crisis to lasting financial well-being.